The balloon fiasco that took place the last two weeks ties in very nicely with the theme I’ve been talking about: countries struggling through “growth spurts.”

China, like the U.S. 120 years ago, is stuck in a state of overreaching, a term first used by Susan Shirk to describe China in her book Overreach. The term essentially describes when a country’s leaders become taken over by special interests such that they stretch the country’s institutional capacity. Often in harmful or self-destructive ways.

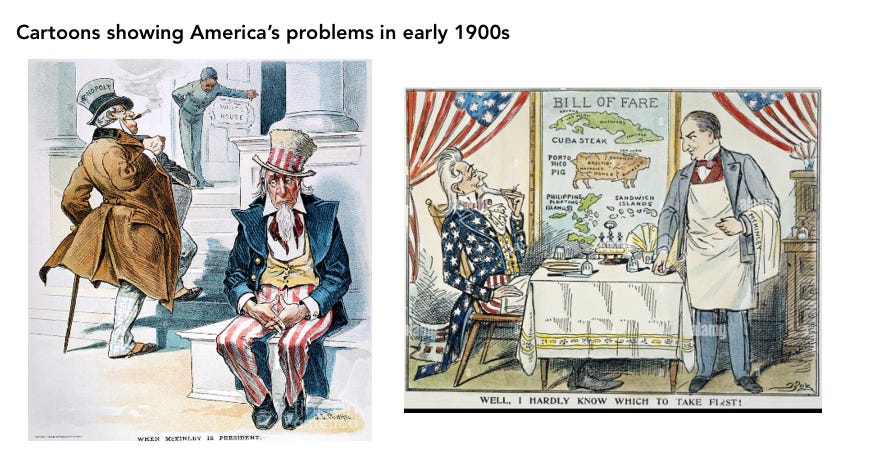

I’d say America at the turn of the century suffered the same problem. It was a quickly growing country with numerous problems like rampant corruption, growing monopolies, intense racial tensions, social stratification, and growing imperialist tendencies. This ultimately caused the government to overreach itself militarily, economically, and politically, engaging in imperialism in the Philippines and Hawaii.

Yet today, we are seeing a similar “overreach” phenomenon in China. The balloon incident is an example of this.

While we may never know exactly the cause of the incident, my best guess is there is likely growing tension within the CCP about how to deal with the U.S. Remember that the CCP absolutely must project unanimity, regardless of what’s going on internally. Dissent within the leadership’s elite is the biggest risk to the Party’s rule. These rules are so strict that apparently Standing Committee members aren’t allowed to socialize with one another; they can communicate only through secretaries. Any hint of dissent or division within the elite ranks can metastasize into a coup. So dissent within the elites is silenced, while dissent within the public is squashed, as evidenced by the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

The CCP has a history of covering up deep divisions within the Party over key policy issues. Recall that China’s Party offices and terms are not regulated by laws. China’s constitution does not mention the rights and responsibilities of China’s most powerful position, the CCP general secretary. Moreover, the nomination and election processes that occur when the Central Committee elects the powerful Politburo, Standing Committee, or general secretary positions are also not a standardized process. Because of this, power is constantly shifting and fluctuating between elites.

Without laws codifying leadership behavior, the rules of the Serengeti take over. Power comes through loyalty. The more people you have loyal to you, the more defenders you have, and the likelier you are to survive - and thrive - in the Party’s inner circle. This dynamic also tends to create factions coalescing around generally two or more poles of power.

Back during the Hu era during the 2000s, Party loyalty was clearly split between two factions. As I’ve said before, the first was called the “second generation reds [红二代],” also called the “princelings,” who were the sons and daughters of China’s Communist party founders. The other group was called the “Youth League” faction [团派], which included Party members such as President Hu himself as well as Premier Wen Jiabao, who entered the Party through hard work, fierce loyalty, and stellar policy performance.

Back then, the Youth League faction endorsed more “democratic-like” and economic-liberalization reforms. Premier Wen in fact came out once and bluntly said “science, democracy, rule of law, freedom, and human rights are not the sole domain of capitalism.” It was during the Hu era that China made its most experiments in democracy and rule of law.

But President Hu made numerous mistakes, which contributed to the Youth League faction losing favor in 2012. This was evidenced by Standing Committee members becoming too powerful during Hu’s reign (“becoming like feudal lords to the king,” as noted on insider in Shirk’s Overreach book). Interest groups linked to industry slowly began to take over power, particularly in the defense and maritime industries. Because the system was so opaque, it took years to fester and grow. But fester it did, and by 2012, Premier Wen Jiabao’s family had quietly become one of the richest in the world, as reported in the NY Times.

This particular incident gave fodder for the princeling group - where Xi comes from - to take over. This is the reason why President Xi was elected by the Central Committee selectorate, why he cracked down on corruption so hard, and why Party elites supported him so much. Moreover, President Xi himself had been involved in democratic elections during the Hu era as a provincial-level leader, but he didn’t like the outcomes. He was elected Xiamen mayor by the city’s People’s Congress in 1986, for instance, but the CCP Organizational Department objected and nullified the outcome. The Party wasn’t ready for democracy, Xi figured. It needed discipline.

Xi took unprecedented measures to reclaim central Party authority. After Xi came to power, he ordered the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) to jail or punish 3.7 million officials (!). Xi also jailed powerful leaders such as Bo Xilai who were a credible threat to his rule. Central CCP authorities also began appointing judges rather than local-level leaders, firming the Party’s control over local courts.

Due to the corruption linked to Hu, no one dared dissent. After all, no one wanted to look like they were on the side of corruption. Moreover, former President Jiang was too old to mount a defense on their behalf. Some even said he made a deal with Xi to not make public comments in return for not going after him and his family. In May 2022, the CCP Organization Department then issued a directive to “strengthen its political guidance over retired cadres” to make sure that they do “not spread politically negative remarks or participate in illegal social organization activities.”

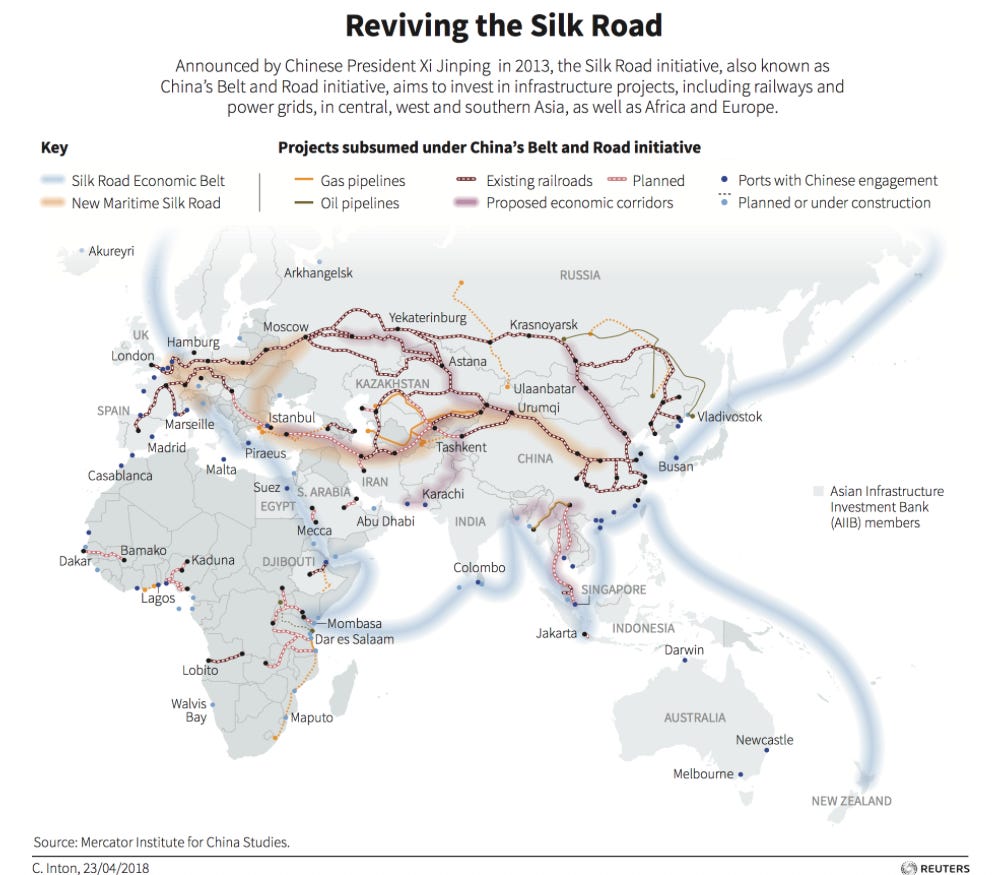

But by this point, security and defense factions had already gained significant influence within the Standing Committee. These factions were linked to China’s defense industries as well as maritime agencies linked to its sovereignty. Martimine agencies specifically lobbied for more resources to protect China’s growing international interests. Xi didn’t seem to mind - after all, these industries play well to the growing nationalist crowd. These agencies also pushed for civilian commercial expansion abroad, which in turn helped lay the groundwork for “military protection” without raising red flags (e.g. as seen in China’s recently built Djibouti military base built on the east coast of Africa). This, in turn, is why China’s “Belt and Road” initiative gained so much favor within the Party.

Competing defense interests in China’s hierarchy have contributed to leadership being pushed in different directions in the past. Public clashes between China’s defense complex and China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) are not uncommon. Back in 2007, for instance, a U.S. aircraft carrier had been scheduled and approved by China’s MOFA to moor in Hong Kong for Thanksgiving break. But the Central Military Commission revoked the decision last minute, forcing the ship to divert to Japan. Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechu was visiting Washington and tried to smooth over the situation by linking the mishap to “poor communication.” But then China’s Foreign Ministry claimed the decision was actually done out of spite linked to President Bush’s earlier visit with the Dalai Lama, leaving the American side hopelessly confused about what was going on.

Today, it’s believed China’s military and defense-related interests have begun to increase their influence within the Standing Committee. While MOFA is known to not be a powerful organ within Party leadership, the most recent spat suggests their influence is now waning even more. Meanwhile, we know that the Chinese military has had a growing interest in the use of balloons for military purposes. We know, too, that China has sent balloons over U.S. airspace in Florida, Guam, and Hawaii in the past, so using balloons for reconnaissance is a tested Chinese military tactic.

So with all this, the exact purpose of the balloon will likely be debated. Perhaps the balloon could intercept radio communications conducted between nuclear silo sites in Montana, Wyoming, and Washington DC. Or, the balloon could potentially be collecting cellphone communications - e.g. radio frequency identifiers - linked to personnel manning the silo sites. That data may have been collected along with the help of a van that transversed the area at the same time. Correlating this information with other data they already have, Chinese intelligence could potentially use creative ways to gain access to silo personnel’s cellphone data.

One wrinkle remains, however. Allowing this three-bus width balloon to float at 60,000 feet, in addition, tells us the issuer of this balloon knew it would be spotted by U.S. civilians.

With this tidbit in mind, the exercise may also have been a test of how the U.S. deals with close-flying objects of Chinese origin. After all, the U.S. regularly conducts surveillance operations near the east coast of China, which certainly sparks controversy within Party leadership. Inducing the Americans to shoot down a Chinese balloon sets a precedent for the Chinese military to shoot down U.S. planes close to their territory. And it certainly showed the Party how Republicans used the incident as a political tool to divide the country. Tit-for-tat.

Either way, the incident seems to suggest China’s Standing Committee is increasingly adopting a more defensive posture when dealing with the West. There are increasing forces within China’s leadership that do not want U.S.-China relations to improve. They are increasingly disregarding any voice of reason within MOFA. They are becoming bolder and more risk-taking. And, perhaps even more disturbing, they are earning Xi’s blessing - or they are coming from Xi himself - which bodes for even darker times for the U.S.-China relationship in the months ahead.

Disclaimer: BubbleCatcher is published as an information service for subscribers, and it includes opinions as to forecasts on the global economy and its impact on securities linked to economic activity. The publishers of BubbleCatcher are not brokers or investment advisers, and they do not provide investment advice or recommendations directed to any particular subscriber or in view of the particular circumstances of any particular person. BubbleCatcher does NOT receive compensation from any of the companies featured in our articles. At various times, the publisher of BubbleCatcher may own, buy or sell the securities discussed for purposes of investment or trading. BubbleCatcher and its publishers, owners, and agents are not liable for any losses or damages, monetary or otherwise, that result from the content of BubbleCatcher. Past results are not necessarily indicative of future performance. The information contained on BubbleCatcher is provided for general informational purposes as a convenience to the subscribers of BubbleCatcher. The materials are not a substitute for obtaining professional advice from a qualified person, firm, or corporation. Consult the appropriate professional advisor for more complete and current information. BubbleCatcher makes no representations or warranties about the accuracy or completeness of the information contained on this website. Any links provided to other server sites are offered as a matter of convenience and in no way are meant to imply that BubbleCatcher endorses, sponsors, promotes, or is affiliated with the owners of or participants in those sites, or endorses any information contained on those sites unless expressly stated.